Mysterious Winds Cause Rapid Melting of Antarctic Ice

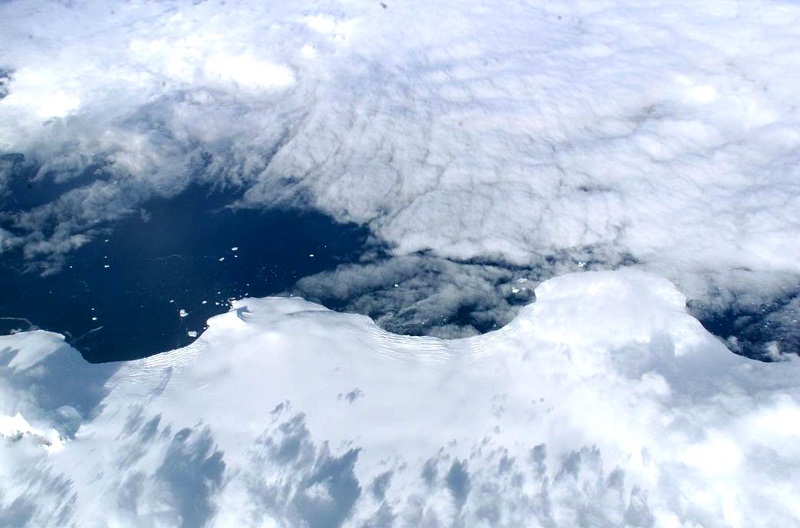

A peculiar storm swept across the mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula in February of this year. Several scientists hunkered down in their tents as a torrent of horizontal-blowing snow washed through. Erin Pettit found her way through the camp by following a series of red and green canvas flags flapping on bamboo poles. But when she paused and looked up, she saw something strange: a circle of blue sky directly overhead. It revealed that no new snow was actually falling—the blizzard consisted entirely of recycled snow—a thin layer of it, only a few feet thick, blowing along the ground. The wind had scoured this snow off the surfaces of glaciers as it accelerated down the east side of the Peninsula’s mountains. When the winds finally let up, Pettit emerged from her tent to find the snow mushy beneath her boots. The temperature had topped 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Training her binoculars on the lower reaches of Starbuck Glacier, six miles to the east, she saw that it had taken on a bluish tint: The wind had melted enough snow to form hundreds of ponds on the glacier’s surface. It was just the sort of observation that Pettit and three other researchers had come here looking for. After studying Antarctica’s warming climate for decades, scientists are making a surprising discovery: In some places, much of that abnormal warmth is invading in the form of powerful, downhill winds called föhn (pronounced “fone”) winds. Pettit, a glaciologist from the University of Alaska in Fairbanks and a National Geographic explorer, now suspects that these winds contributed to a series of dramatic glacial collapses that have been steadily redrawing the map on the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula for the last 30 years. Föhn winds may have escaped scientists’ notice because they don’t just blow during summer—some of their most impressive heat waves actually strike in the dead of winter, eroding glaciers at a time of year that no one thought possible.